Omar Henry has revealed how he wanted to return home from the 1992 World Cup after being given what he considered an unsatisfactory answer over why he was left out of South Africa's match against New Zealand. In an emotional testimony at Cricket South Africa's Social Justice and Nation-Building (SJN) hearings, Henry revealed how he was regarded as a "sell out" by his own community after he accepted an offer to play for a white club in the 1970s, and the challenges of being the first player of colour to represent South Africa post-readmission in 1992, including his difficulties at the World Cup, which he believes reflect selection issues that continue to exist today.

Henry was the only player of colour included in South Africa's squad for the tournament, and the only specialist spinner. He played just one match, against Sri Lanka in Wellington, despite South Africa's schedule featuring three group matches in spinner-friendly conditions in New Zealand. "I did my research and knew as the frontline spinner that I was not going to play that many games because of the conditions and the way our squad was selected, because we were stacked with a lot of allrounders. I made peace that I would be lucky if I played one or two games. But when I saw New Zealand play in New Zealand and I saw there was a pitch that was going to suit me, I had high expectations that I would play," Henry said.

He didn't.

"I wasn't selected. I was very disappointed and I needed to know why I wasn't selected. I went to the manager and asked him if he could give me a reason why I wasn't selected, which was the protocol. He said, 'I know you're disappointed and I will talk to the captain and the coach and I will come back to you.'"

By match-day, Henry had not received a response and after South Africa's defeat, was involved in "an incident," with captain Kepler Wessels. "We played the game, we were absolutely annihilated and everybody was upset. In the dressing room an incident happened between me and the captain and it created a very unpleasant situation that eventually had to be stopped by the manager," Henry said. "I was unhappy with the way I was treated and the answers that were given to me so I pursued the matter further. Several meetings were held, and still I wasn't satisfied and then I wanted to come home. I wanted to leave. That created even more tension." It was only the intervention of CSA's first president of colour that convinced Henry to stay. "I managed to find out that Krish Mackerdhuj was in Australia and I requested a meeting with him. I explained my situation and said I wanted to go home if I don't get the right answers and he pleaded with me that there is a bigger picture and I can't go home," Henry said. "He was of the view that if I go home, there is no guarantee that things like this won't happen with players of my colour in the future. He pleaded with me for a few hours and I changed my mind and stayed. I felt that maybe it was meant to happen to me as the first black person to play for South Africa, and hopefully that will be addressed and we will move on. In hindsight, I was wrong. That's why we are here today."

Henry spoke of happier times when he played for the Free State province, a historically white, Afrikaans team, who embraced him.

"Afrikaaners felt they were given a raw deal, just like black people, although they enjoyed the privileges of Apartheid. My stay in Bloemfontein was an education in how liberal some of those Afrikaaners were and I made friends for life," Henry said. "We won the Currie Cup and it was the last year of the Currie Cup. That was a great achievement. When I look at my contribution to that, trying to prove to the white man that a black man can also play cricket and that we can all live together in peace and harmony and respect one another, I felt in my heart that I broke down barriers. And I think I did. Those players and people that were close to me, we still had respect for one another although we come from different backgrounds. They knew, in their heart of hearts, that Apartheid was wrong."

Henry also saw continued challenges in selection, specifically relating to racial bias when he worked as an administrator. He coached Boland and was a selector at the province, and also served as selection convener for South Africa between 2002 and 2008. Throughout that time, Henry had to work within the confines of the target system which stipulates the minimum number of players of colour that a domestic team and the national side must field.

Henry found the system limited, that it set a bar people were not willing to go beyond and turned transformation into a number-crunching exercise. He provided an example from his time at Boland, when the targets required teams to field three players of colour and he faced resistance when he wanted to pick a fourth player, Henry Davids. "I took the risk and fought for him to be selected, knowing full well that I could lose my job. But I stuck my neck out and that's when the realisation came that there is still some misunderstanding or mistrust or dishonesty within the system," Henry said. "In the dressing room an incident happened between me and the captain [Kepler Wessels] and it created a very unpleasant situation... I was unhappy with the way I was treated... I wanted to come home. I wanted to leave. That created even more tension."

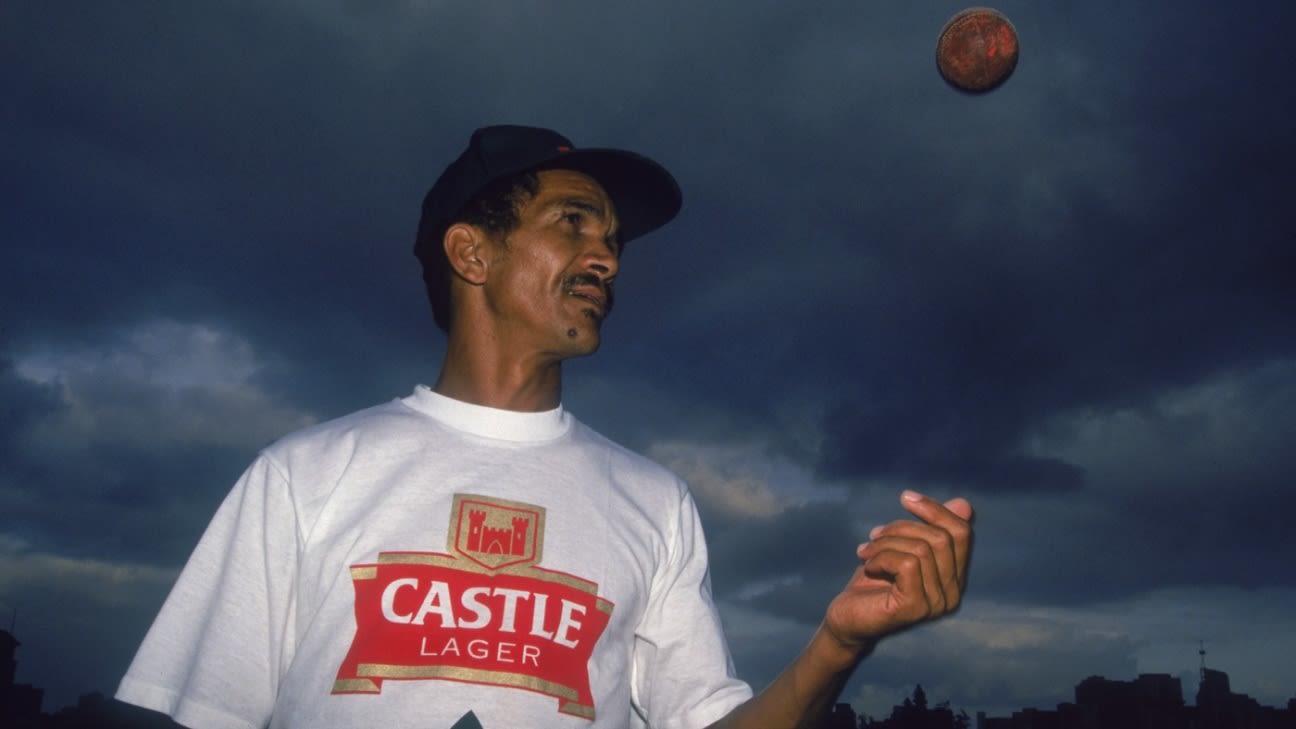

Omar Henry on his 1992 World Cup experience

Henry also said the transformation goals presented to him when he served on the national selection panel were unrealistic and could only be met in time. "I was told I need to pick 50% black players in the team. From what I knew about the system at the time, I couldn't honestly say that I could have achieved that immediately. I had to be honest and say I am sorry I can't deliver on that," he said.

Overall, Henry painted a picture of a sporting system that is grappling to understand how to develop talent as it tries to redress past wrongs. He acknowledged that the pain of people of his generation, a few of whom left South Africa to seek opportunity abroad (Henry played for Scotland for example), and most of whom never got the chances they may have wanted, has not healed and that true inclusivity continues to be elusive.

"There is a lot of hurt. There is a lot of healing to be done. People of my age, at unification, thought they were going to get an opportunity. They didn't. They didn't come close. We don't know the depth of the emotional damage we have done to people," Henry said. "There is a lack of education about understanding what development is, what transformation is. I can talk about this all my life because it was my life. It is not an easy subject and it is something we have to continue and we are probably going to continue this even when my grandchildren are adults."

The SJN hearings are due to run for the next two weeks after which transformation ombudsman Advocate Dumisa Ntsebeza, will produce a report and recommendations to CSA.

Firdose Moonda is ESPNcricinfo's South Africa correspondent

Phone: (800) 737. 6040

Phone: (800) 737. 6040 Fax: (800) 825 5558

Fax: (800) 825 5558 Website:

Website:  Email:

Email: