One-lap legend on the training that led to the Olympic podium and why the sport should tap into the experience of former internationals

You came very close to breaking the European 400m record. Why do you think it is still standing after so long?

The European 400m record of 44.33 was set in 1987 by a great rival of mine called Thomas Schönlebe from East Germany. He never beat me and I only ran against him three or four times. In 1987 he became world champion. I’m surprised the record has stood so long. A few people have had a nibble at it, including myself, Iwan Thomas, Derek Redmond and most recently Matthew Hudson-Smith.

I thought Matthew would break it this year and I think he eventually will if he stays fit. I guess it’s stood so long because it’s a good record but I think it’s time for Europeans to go under 44 seconds. With just the evolution of spikes technology it’s time that the record went. I would predict that it will go within the next year.

What were your longest and preferred training sessions?

The longest sessions were in the winter. We were quite old school back in the day. Myself, Kriss Akabusi, Todd Bennett and a whole host of athletes were down in Southampton in the early days. We would have long two-hour Sunday sessions across sand dunes and beaches, under the guidance of Mike Smith, in all sorts of weather. You’d get in the car, drive back and hope for a Sunday roast at home. That’s where we put the real hard work in.

My preferred sessions were the ones that I knew mattered. You can train loads and loads but there were some key sessions we did for the 400m and you knew when they were coming up. You were always nervous in the morning lead-up to it. They would be two or three runs over 500m and I never enjoyed that, for example, but I knew it was important.

The big one that Kriss and I used to mark where we were [in terms of fitness] would be when we did 4x300m runs. Invariably, we’d be out in California for warm weather training and getting ready for the season.

You had 10 minutes recovery but it was honest running and we would lead each other on every other run. The first one felt great, the second one was pretty good and you’re running at 95 per cent. That 10-minute recovery suddenly feels shorter.

The third one was key and you had a choice, knowing if you went to the line and were honest you’d be in trouble. We’d always go to the line and try not to collapse. This was the session that made us as 400m runners.

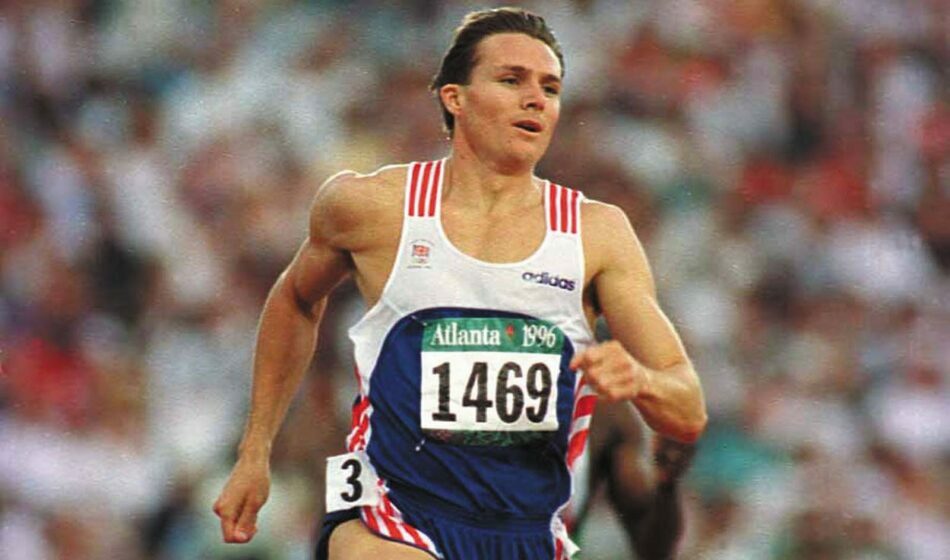

Roger Black (Mark Shearman)

Did you ever think you had a chance against Michael Johnson? If not, what kept you motivated and how did the measure of success change for you?

It underpins everything for me. Michael Johnson came on the scene in 1991 as a 200m runner and then eventually progressed to the 400m. From 1993 onwards he was so dominant. I’d raced Michael a lot by the time it came to Atlanta 1996 and we were definitely friends and had great respect for each other.

I had the choice at those Olympics of trying to race Michael or to run my own lane. I quite famously said that going into the Olympics we were running for second place but what I never said was that I couldn’t win the gold medal.

I knew that Michael was better than me but he could make a mistake. All I could control was how I ran. I didn’t think I’d come second but that was the right mentality. If I had raced Michael I would never have won an Olympic medal and regretted it for the rest of my life. Success for me was walking off the track knowing that I’d performed to the best of my ability. That was reflected by a silver medal.

John Regis, Kriss Akabusi, Roger Black and Derek Redmond celebrate (Mark Shearman)

Do you feel enough has been done in Britain to utilise the experience of former athletes to help the next generation?

I don’t think so. It baffles me, Kriss and Daley [Thompson] for example. Success leaves clues in all walks of life and when I was going through my journey I sat alongside Seb Coe and Edwin Moses to name a few and we would pick their brains.

Any former athlete will always be happy to tell the young and up-and-coming athletes what they experienced and just to sit and listen to people, even knowing that we’re all different, you might pick up something from somebody that is really important.

READ MORE: Relay legends look back on Tokyo 1991

I’ve never really understood why British Athletics don’t structure that into the journey of a young athlete’s progression. I know so many people who would talk.

Steve Backley has talked to the next generation, for example, but not as much as he should have done. We’re not talking about athletes becoming coaches – I’m not a coach and I never would be one – or even a specific mentor but just to share experiences. You can absorb so much from others and even if it’s just one thing that resonates then you can apply that to your training and get an improvement.

Phone: (800) 737. 6040

Phone: (800) 737. 6040 Fax: (800) 825 5558

Fax: (800) 825 5558 Website:

Website:  Email:

Email: