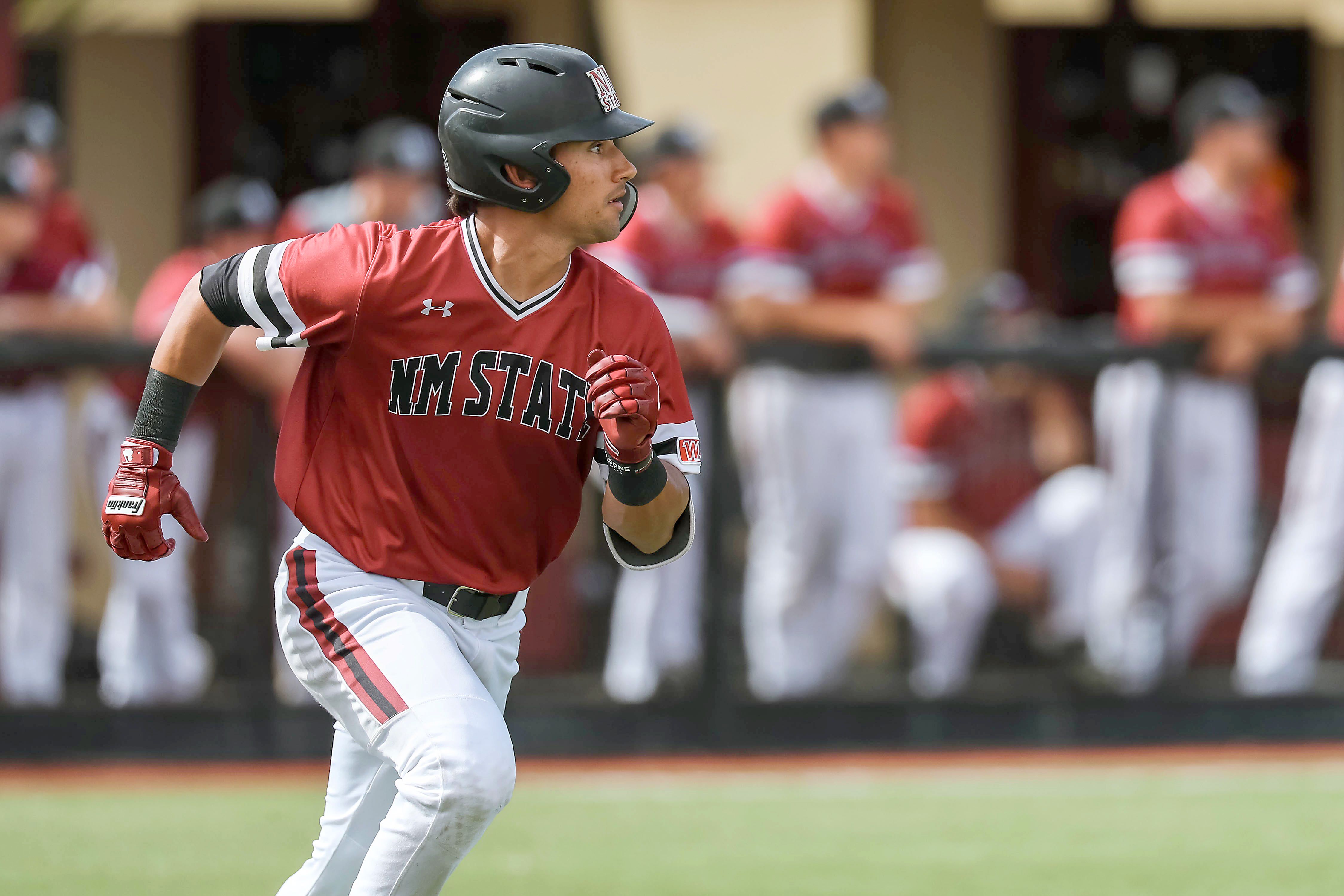

Nick Gonzales secured a .502 on-base percentage through a 128-game collegiate career that has undoubtedly reached its conclusion. He once belted five home runs over the course of one doubleheader. And when the coronavirus pandemic shut down American sports for the foreseeable future, he was riding an 82-game on-base streak that will now just sit there, unblemished for all eternity.

But the most impressive, most telling statistic surrounding Gonzales, the New Mexico State infielder who is all but certain to be a top-10 pick in this year's MLB draft, is much simpler than that: During an entire summer in the Cape Cod League, through 185 plate appearances and countless rounds of batting practice, he broke just two bats.

Mike Roberts has coached 18 seasons in the Cape and has consistently seen amateurs struggle to transition from aluminum bats to wood, the latter of which has a special way of exposing flaws within a swing. Strike the baseball anywhere outside the heart of a barrel that measures no more than five inches, and usually that chiseled piece of ash is rendered useless. Roberts, who coached Gonzales for the 2019 Cotuit Kettleers, has urged players to use a different bat in a game than they would in practice. In a typical summer at the Cape, he expects his regulars to break a minimum of 12 to 15 bats. Two?

"I mean, I went through maybe like two a week," said Adam Oviedo, a TCU infielder who played shortstop for Roberts last summer. "I had a wood bat break on me when I just went to home plate and tapped on it and I said, 'What the heck?'"

Full coverage of the 2020 MLB draft is available here

Watch the 2020 MLB draft on ESPN & the ESPN App

Wednesday: Round 1 starting at 7 p.m. ET (ESPN)

Thursday: Rounds 2-5 starting at 5 p.m. ET (ESPN2)

Kiley McDaniel's latest mock draft

Team-by-team draft guide: Fits, needs for all 30 teams

Ranking the top 150 MLB draft prospects

Gonzales was hardly on the national radar when he joined the Kettleers and became Oviedo's double-play partner last summer. The incredible numbers he had compiled through his first two seasons at New Mexico State were mostly dismissed because of the inferiority of the Western Athletic Conference and the hitter-friendly environment of his home ballpark, which sits at an elevation of nearly 4,000 feet. Major league scouts needed to see Gonzales perform in a more neutral environment -- against better collegiate arms, with a bat made of wood.

"I kind of went in there knowing that, but when I got there I just played the game," Gonzales said. "Fortunately, I played well."

Gonzales, 21, batted .351 with 25 extra-base hits in a 42-game, championship-winning season that major league executives will cling to in a year devoid of meaningful stats from amateurs. Midway through the playoffs, with his team down a run in the bottom of the seventh and 3,000 people crammed into a small ballpark, Gonzales worked the count full and blasted a two-run homer to straightaway center field. The following night, in the opener of a best-of-three final round, Gonzales came up with two outs and runners on the corners in the top of the 15th and lined an 0-2 offering up the middle for the winning hit.

After it was over, Roberts gathered his players in the dugout and passed around a sheet of paper so they could vote on the league's MVP. His catcher, Cody Pasic, stated that it wasn't necessary. He looked around the room.

"Guys," Pasic hollered, "who's the MVP?"

"Nick Gonzales!" they blurted out in unison.

"Nobody even wrote anything on the paper," Oviedo said. "It was just that clear."

There were rumors floating around the Little League circuit that Nick Gonzales was utilizing a juiced bat because few could understand how somebody so small could hit a baseball so far. His father, Mike, once found himself within earshot of two friends whispering the claim to themselves after another titanic home run and decided he was fed up. He offered a bet: $500, and he'll saw his son's bat in half to settle this once and for all. They backed off.

Another allegation was made on Facebook when Gonzales was only 12. His older brother, Daniel, who went on to become a star linebacker at Navy and is now stationed in Okinawa, Japan, felt compelled to reply. He wrote about all those nights when his little brother returned from games and decided he needed to hit some more, and all those mornings when Mike would get up at 5:30 and find Nick hitting baseballs into a net in the garage. Daniel's message, basically: If only you knew how hard this kid worked.

"My wife says he's got an obsessive compulsive behavior," Mike Gonzales said of his youngest son. "Whatever he latches onto, that's all he does -- and it's been baseball for a long time."

There are concerns about Gonzales' size -- he's listed by New Mexico State at 5-foot-10, 190 pounds -- and his throwing arm. The belief is that he won't be better than an average defender who might be good enough to hold his own at second base but won't be able to play shortstop at the major league level. But people rave about his work ethic and discipline -- and few now question his ability to hit.

Roberts, a longtime coach at the University of North Carolina, compared Gonzales' rhythm and balance to that of Miguel Cabrera and Manny Ramirez. Oviedo marveled at Gonzales' unrelenting plate discipline. New Mexico State coach Mike Kirby noted his ability to spot tendencies in split seconds, like how the angle on a pitcher's wrist will shift slightly as he prepares to throw a breaking ball. But the separator is his hand speed.

"Off the charts," said Casey Schmitt, who played third base on last year's Kettleers team. "I've never seen anything like it."

Gonzales was a little uphill at the point of contact and struggled to drive pitches to the opposite field when he reached college. Brian Green, the former Aggies coach who's now at Washington State University, brought his top-hand elbow down, raised his hands and put him in position to get into his swing more quickly. It accentuated Gonzales' inherent hand speed, which allowed him to maximize the amount of time he could spend watching pitches travel before reacting.

While he was tearing it up in the Cape Cod League and thusly shooting up prospective draft boards last summer, Gonzales sent Green a photo. It's a side image of a baseball no more than 18 inches from reaching home plate. Gonzales is still in the early part of his swing path, with the barrel of his bat at the level of his right shoulder -- for a pitch he ultimately drove. To Green, it's a photo indicative of the trait that makes Gonzales a special hitter, regardless of setting.

"Nick knows, and has learned, that he can wait a very long time before he has to make a decision," Green said. "And that's what makes him elite."

Mike Roberts' son, Brian, stood 5-foot-9 and weighed around 175 pounds during his playing days. He wasn't heavily recruited out of high school, but he went on to make two All-Star teams and carve out a 14-year major league career -- predominantly with the Baltimore Orioles -- by working harder and becoming more polished than most of his peers. When Mike watched Nick Gonzales, he saw his son.

"When you're not recruited very much, you have a humility that a lot of people don't have, particularly outstanding players," Mike Roberts said. "And I think that's the first thing that stands out about Nick is his humility. Youngsters that are humble first and haven't been told as they come through all the travel ball leagues how good they are every day -- they have a humility and a self-motivation and a love of practice because they've had to outwork most of their peers to get there."

Gonzales hit .543 during his senior year for Cienega High School in Vail, Arizona, but the University of Arizona didn't pay much attention to him. Mike Gonzales initially thought his son would go to Grand Canyon University based on his conversations with its head baseball coach, but nothing materialized. Austin Peay State University in Tennessee was the one school that kept pushing, offering a scholarship package typically reserved for highly sought-after pitchers. But Gonzales wanted to remain close to home. On a free weekend, Nick and Mike toured New Mexico State on their own and scheduled a meeting with then-coach Brian Green, who offered his typical 90-minute PowerPoint presentation but also cautioned that he had no more money to offer.

"They don't think I can play," Nick told his father on their way back home. "I'm gonna show them."

Nick transformed his body when he left high school, putting on an estimated 15 pounds of muscle over the course of his freshman year of college. The ball suddenly began to jump off his bat. Green initially thought Gonzales would redshirt as a freshman, but Green wound up starting him for 53 of the Aggies' 62 games. Gonzales led the team in batting average (.347) and led the conference in slugging percentage (.596), ultimately becoming the first WAC freshman of the year in New Mexico State history. Throughout the spring, he played with the acronym "PTAW" written on his glove -- "Prove Them All Wrong."

Green had spent a quarter century coaching in the collegiate circuit by that point, at small schools like Riverside City College and major programs like Kentucky.

"That type of development, right in front of your eyes, I had never seen it," Green said. "It was mind-blowing, to be quite honest."

Gonzales went on to hit .432/.532/.773 as a sophomore in 2019 and .448/.610/1.155 during his abbreviated 16-game junior season in 2020. He finished his collegiate career with a 1.249 OPS and 10 more walks than strikeouts. But it was one summer on Cape Cod, Massachusetts, that changed everything.

Gonzales understood the moment but didn't obsess over it. Roberts referred to it as "a quiet motivation." Mike Gonzales watched the first few games on a livestream and wondered why his son seemed so passive at the plate. He asked what was wrong, and Gonzales explained that he was still feeling his way through. The window was small, the pressure was obvious, but first he needed to acclimate himself.

"And then suddenly it just clicked," Mike Gonzales said. "I was just in awe the whole time."

Phone: (800) 737. 6040

Phone: (800) 737. 6040 Fax: (800) 825 5558

Fax: (800) 825 5558 Website:

Website:  Email:

Email: