While the first wave of NBA teams prepare to reopen facilities for individual workouts on Friday, several team officials say the psychological effects of returning to organized activities during a global pandemic must be considered for players and staffers around the league -- especially those who already have a heightened concern about germs.

Several general managers and athletic trainers pointed to a number of players -- though they say it's not a large percentage -- who they would describe as "germophobes." These team officials say there are several executives and other league staffers in the same position.

"I'm one of them," one veteran front-office executive for a team in postseason contention told ESPN.

Said one Eastern Conference general manager: "I'm not a germophobe, and I'm afraid."

Several team officials said there are players and staffers on their respective teams who fit that "germophobe" description, though none felt comfortable sharing their identities -- and none faulted them for being extremely cautious on that front.

But multiple Western Conference athletic training officials referred to this psychological impact as a powerful added stressor for some players that could no doubt inhibit their ability to perform, even if the NBA was able to create an ideal environment at some point in the near future.

"Some players will have an easier time breaking through that, and other players will have a real challenge with that," one Eastern Conference athletic training official said.

Mental health was once a taboo subject in the NBA, though that has changed in recent seasons. A memorable turning point came when former NBA All-Star Metta World Peace publicly thanked his psychologist after the Los Angeles Lakers won the 2010 NBA title against the Boston Celtics.

In regard to the current psychological challenge that players would face if play is resumed, World Peace said it is no small obstacle.

"People are affected when humans are affected, because we're only people," World Peace said in a phone interview. "... If one of your significant others passed away, you might mourn for a year or whatever. Now, you got 50,000 to 60,000 people passing away all over the globe -- that's going to mess with anybody. You just never know who it's going to affect. On a certain level [guys will think], 'What if I get it? What if I don't?' You just never know who's it gonna affect."

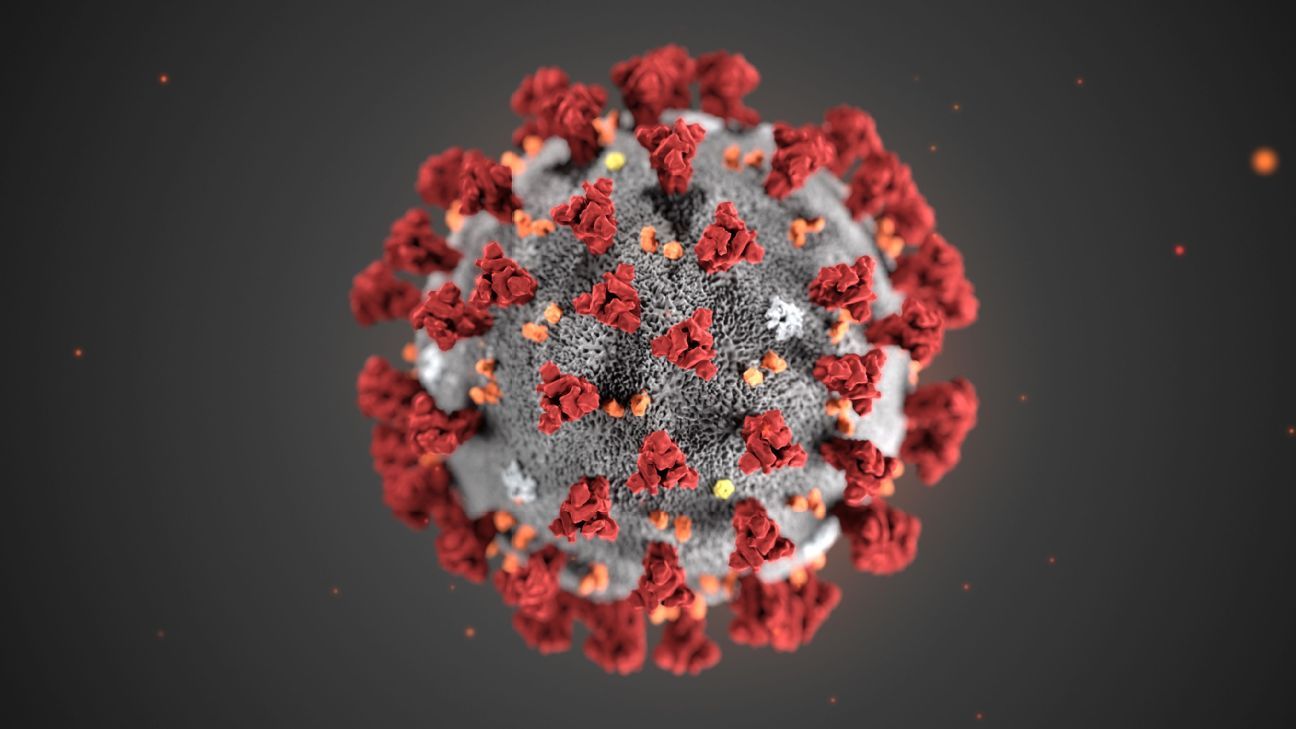

More than 250,000 have died during the coronavirus pandemic, including more than 75,000 in America.

That psychological challenge extends to team staffers, too.

"I just know myself," said the athletic training official for a Western Conference team. "I wouldn't want to work with the [players]. I mean, these are young guys. Some of them, I don't think they think it's real. They're just like, 'Oh, we're thinking too much into it,' but I'm like, 'It's the whole world.'

"And so the tough part is, it's my job to work with the guys. So you don't want to go against the grain, but at the same time, I'm not trying to put my family at risk."

If, in fact, some players are ultimately uncomfortable being on the court -- and, thus, breaking social distancing guidelines -- then a number of team officials said they expect that feeling will dissipate in time, especially as financial losses mount.

"I think as soon as checks are impacted negatively," said one Western Conference general manager, "guys are going to get over any concern they would have for returning to play."

Added one Eastern Conference general manager: "There are always going to be people, when they have the ability to put up a fight against certain things they hear about, they're going to do it. Then, when somebody says -- 'Well listen, this is what the deal is, and if you don't do it, you don't get your paycheck' -- now you find out how serious they really were."

One general manager for a team not in playoff contention said that, ultimately, there is likely to be unease about resuming competition. However, the GM said, "I don't think you're going to force anybody. This isn't the time to kind of mandate things. People are going to have to feel comfortable."

The GM likened the experience to the period after the 9/11 terrorist attacks. Some felt comfortable flying immediately, some didn't.

"It's also very personal," the GM said. "You have to figure out and be sensitive and acknowledge that everybody is going to approach this thing differently and just kind of be aware of that and do your best."

In terms of unease on the court, multiple team officials drew loose parallels to the period in the NBA after Earvin "Magic" Johnson tested positive for HIV in November 1991. Questions and concerns soon arose about whether it was safe to be on the same court as the Lakers superstar.

"They can't tell you that you're not at risk, and you can't tell me there's one guy in the NBA who hasn't thought about it," Utah Jazz forward Karl Malone said then.

"Everybody's talking about it," Cleveland Cavaliers guard Gerald Wilkens said then. "Some people are scared. This could be dangerous to us all."

Cavaliers guard Mark Price went so far as to say that he didn't want to play against Johnson.

Even in Johnson's own locker room, questions mounted.

"His own teammates were coming to me behind his back, asking me, 'Are you sure we can't get this?'" former Lakers head athletic trainer Gary Vitti recalled recently. "[They would say] 'These other guys play against him a few times a year; I've got to practice a few times a day.'"

And, Vitti said, part of his job became "to try and take that out of their minds [and say], 'No, you can't get it that way.'"

To be clear, none offered any direct comparisons about the dangers of HIV or AIDS as it relates to the coronavirus or Covid-19.

"I don't think there's a corollary to Magic Johnson and what he dealt with," one general manager for a team in the playoff hunt said, "but, because this one is so contagious, there's still the psychology around it."

As Vitti looks at the situation now, he thinks of the differences and parallels to what the league was facing with Johnson's situation in 1991.

"It's comparing apples and oranges," Vitti said. "Covid-19 is much more contagious than HIV, but the death rate is much lower ... [and] they can transmit it to somebody else who eventually transmits it to someone who dies and we can't have that.

"The fear is there and it's real, but this is a different situation. You have a responsibility to the people down the line that you're passing it down to, and that needs to be taken seriously."

Phone: (800) 737. 6040

Phone: (800) 737. 6040 Fax: (800) 825 5558

Fax: (800) 825 5558 Website:

Website:  Email:

Email: